It is out of this penchant for storytelling that legendary myths grow. Stories are not just told, but retold, and in the retelling, human beings have a tendency to exaggeration. Exaggeration amplifies the impact and intrigue of a story, and in the process the status of the teller (as the saying goes, don't let the facts get in the way of a good story). Through several iterations of retelling and exaggeration, feats of ordinary human heroism, such as success in battle, can morph over time into the actions of quasi-gods, such as the slaying of three-headed dragons, and in the process become increasingly untethered from the original facts. But we don't care. Willful suspension of disbelief is one reason human beings enjoy movies so much. We like a good story.

The human penchant for storytelling, exaggeration, and a preference for exciting narratives over more mundane facts, manifests repeatedly in markets. Stories are intuitive, interesting, and have clear actionable messages, and so are easy to sell. Abstract data and raw facts, by contrast, are often complex, messy, and conflicting, and more difficult to intuitively relate. This is why cheap stocks are invariably those with an unappealing narrative, while the most expensive and popular issues of the day are generally replete with all kinds of exciting growth narratives. This is what captures peoples' imaginations. And a lot of the time, people become so captivated with stories, that they tell (and retell) them without bothering to check the facts.

This lack of fact checking also has numerous other causes, including a scarcity of time, and simple intellectual laziness. A calorie-scarce environment throughout evolutionary history has not endowed human beings (or any creatures) with a tendency to exert unnecessary effort. This is why going to the gym can be difficult. Lions lie around all day, if well fed, for good reason - why waste energy unnecessarily? Intellectual laziness is the same (I seem to be immune from the latter, but definitely not the former). Fact checking is hard work and most people simply can't be bothered.

Another cause is that human beings like comfortable fictions that simplify the world down into a workable world view. It is not psychologically comfortable to live in a mental state where you realise everything you think you know to be true could well be wrong. It results in a feeling not just of confusion, but also of powerlessness, anxiety, insecurity, and fear, and in some cases, identity crises. As a result, human beings create belief systems that make the world seem more predictable, safe, and controllable, even if those belief systems are not strictly rational.

Religion, for instance, offers this psychological comfort to many. It is interesting that in many developing economies, as incomes grow and urbanisation increases, religious affiliation actually increases rather than decreases - the opposite of the secularising influence many might have assumed would accompany modernisation. This occurs because urbanisation is highly disruptive to traditional community-based ways of life. A culture of individualism and self-reliance can feel foreign and deeply uncomfortable.

In this more disorienting milieu, the appeal of a system of moral guidance and community increases. It makes life seem more ordered and safe, and it also allows people to outsource a lot of their thinking on complex moral questions to an off-the-menu template that offers unequivocal, black and white answers to many of life's most vexing questions. It's much easier to take on board comfortable fictions than it is to constantly second-guess yourself and your beliefs, and fact-checking/scepticism is therefore instinctively resisted. It's human nature.

Greek myths

With this context in mind, it is worth highlighting a great example of this human penchant for storytelling, exaggeration, and the lack of willingness to engage in fact checking, that is manifesting in markets at the moment, which is the narrative surrounding Greece and some of the Greek banks (Eurobank is the focus of this article). I am long Eurobank and have been buying fairly aggressively in the past few days.

Greek bank share prices have been crushed this year, and have hit new all time lows, and this has contributed to, and amplified (in a reflexive manner), many longstanding narratives. There are many archs to this story - some new, some old. Longstanding ones are that Greece is forever the hopeless child of the EU; that its government is irreparably insolvent; and that its banks, carrying non-performing loans on their balance sheet representing some 40-50% of total loans (€90bn Euros in total across all four major banks), are walking-dead institutions that will inevitably be in need of perpetual recapitalisation.

Added to these narratives have been some new story archs of late. Firstly, Greece has backtracked on targeted 2019 pension reforms (further reductions). Coming alongside recent developments in Italy, where its new government has pushed back against further austerity and defied obligatory fiscal deficit reduction targets, people have merely assumed that Greece's situation is exactly analogous, and that the government is refusing to cut spending to meet agreed-upon deficit and debt reduction targets. With government debt to GDP of 180%, this unwillingness to exercise budgetary discipline means the Greek state is assuredly bankrupt.

In addition, Greece has recently announced a tentative plan to remove up to half of the bad debts currently held on Greek bank balance sheets via the establishment of an SPV, that would acquire the loans at their carrying value, in exchange for the tendering of the considerable deferred tax assets owned by Greek banks. This measure, in combination with the seemingly neverending downward spiral in Greek bank share prices this year, has lead many to assume this to be merely a futile and desperate act of financial engineering aimed at avoiding what will inevitably prove to be the latest installment of the Greek tragedy. Adding to the sense of malaise, MSCI has announced it will be removing Greek banks from some key indices, which is forcing passive tracker funds to dump the stocks.

The below article from the Telegraph, published on the 21st of November 2018, gives some flavour for the general sentiment. It reproduces in full the sections pertaining to Greece (those pertaining to Italy are omitted):

Greek Crisis Returns as Italian Banks Enter the Danger Zone

(Telegraph) -- Greece’s financial crisis has come back to

the boil as Athens draws up emergency plans to stabilize the banking system,

raising concerns that the country may ultimately need a fourth EU rescue to

escape its depression trap.

Global risk aversion and contagion from Italy’s parallel

banking drama has lifted a lid on the festering legacy of bad debts, and

exposed the implausible methods employed by Greek regulators and the EU-led

troika to camouflage the problem.

Greek bank shares slumped a further 6pc on Tuesday after

five days of falls. They are now down by 60pc since May, chiefly on fears of

drastic state intervention to shore up thinning capital buffers. The Athens

bourse has lost a third of its value this year....

...Greece’s fresh drama has crept up on markets almost

unawares. Most investors thought the eight-year crisis had been put to rest

with the end of the EU’s third rescue programme in August , even though the

International Monetary Fund warned that Greece was still fundamentally

insolvent without full debt relief. It said the country “could struggle to

maintain market access over the long run”.

“Greece is very unstable and will be blown out of the

water immediately if anything goes wrong in the global economy or if there is

a European recession,” said Professor Costas Lapavitsas from London

University (SOAS).

“The Greek banks are walking dead. Credit has been

shrinking every single month and they are not providing the normal function

of banks in an economy. They have been burning up their capital and there

isn’t a penny for recapitalisation. When the real music starts this will

become obvious,”he said.

Prof Lapavitsas said lenders had been allowed to discount

the value of deferred tax credits for 20 years and deem this capital in a

“smoke and mirrors” operation. They are now close to exhausting even this

expedient. “It is not real capital. The Greek state is going to have to step

in and provide cash,” he said.

In effect, the ‘bank sovereign doom loop’ that has so long

bedevilled the eurozone is still working its curse. The Greek central bank is

exploring a variety of options, including the creation of a bad bank or

special purpose vehicle (SPIV) to soak up half the bad debts of the four

systemic banks, Piraeus, Alpha, Eurobank and National Bank.

Non-performing loans are still €89bn. Bonds issued by the

SPIV will in effect require a guarantee from the Greek state. “The whole

thing is a con. It is unbelievable that they are doing this. The bottom line

is that Greece should not be in the euro,” he said.

North European banks no longer have any significant

exposure to Greece. In financial terms, the latest jitters are a local

affair. But the political fall-out would be serious if it became clear that

the EU authorities had yet again misjudged the gravity of the situation when

it declared ‘mission accomplished’ amid much celebration earlier this year.

Critics say the northern creditor powers have refused to

accept that austerity overkill from 2010 to 2018 has done so much damage to

the Greek economy that nothing short of a massive debt-write off, backed by a

New Deal investment blitz, can restore sustainable growth. There will be a

political storm if events in Greece once again leave Europe having to pick

between the twin poisons of Grexit and another rescue...

|

__

Sorry to be a buzz kill, but there is one important problem with this narrative - it simply isn't supported by even a cursory examination of the facts. It takes no analytical brilliance - just a willingness to take a fresh look. One would hope journalists would feel compelled to check the facts before publishing, but no such luck. Some things are too obviously true to require fact checking, it would seem.*

The above narrative begins by declaring that Athens is "drawing up emergency plans to stabilise the banking system", but this merely asserts that the system is not currently stable, without providing any evidence. A lot of the conclusions and inferences subsequently drawn depend on this premise. In fact, the only thing that is not stable at the moment are banks' share prices. Everything else looks fine. And share prices reflect perceptions - created by media articles just like this one - not reality. Often the two are the same, but occasionally they can widely diverge.

Instead of telling each other stories, let's simply take a look at recent trends in Eurobank's financial and operating performance. First and most obviously, while it might come as a surprise to many people, the company is actually profitable, and has booked bottom line earnings of about €50m a quarter for five consecutive quarters. Nevertheless, even if that fact was uncovered, it would no doubt be ascribed to an accounting fiction and a failure to recognise bad debts.

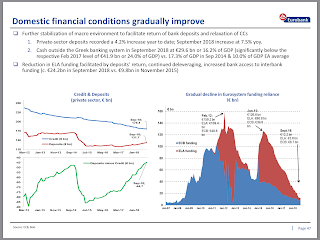

Secondly, let's have a look at liquidity trends. As can be seen below, since the (genuine) liquidity crisis of 2015, Greek system deposits have steadily increased, while system reliance on Euro funding, including ELA funding lines (Emergency Liquidity Assistance), have steadily declined, and that decline has continued in recent months, not reversed. For Eurobank specifically, it's deposit inflows have continued, and its net loans to deposits ratio has now fallen to 95% (down from 99% QoQ, and from 112% YoY), which has seen the company's reliance on Eurosystem funding decline virtually to zero. There is certainly no 'liquidity crisis' here - to the contrary, liquidity is clearly improving.

System Eurofunding has declined and deposits increased; indeed ELA

(emergency liquidity assistance) reliance has been almost entirely removed

Eurobank's deposits have grown and LDR has significantly improved and is.

now below 100%. Falling loans and rising deposits is very positive for liquidity.

Thirdly, what about bad debt trends? Far from careening towards a new crisis, Eurobank has now booked eight consecutive quarters of negative NPE (non-performing exposure) formation - i.e. the pace of 'cures' is exceeding the inflow of new defaults. The pace of net cures slowed somewhat in 3Q, but this was for seasonal reasons, and management noted on its recent 3Q conference call that they were expecting a significant increase in net negative formation in 4Q18 (which was said to be tracking much stronger than 1Q and 2Q), and so could well approach €500m.

In conjunction with other bad debt resolution mechanisms (sales, write-offs, and collateral liquidation), Eurobank has actually reduced its stock of NPEs by €2.4bn Euros in 9M18, and its ratio of NPEs has fallen from 44.7% to 39.0% YoY (and down from 40.7% QoQ), all while remaining solidly profitable. A separate debate can be had about the adequacy of its level of capital and stock of provisions with respect to these legacy bad loans (see further below), but that is not new news, and things are clearly getting much better, not worse. And if Eurobank's declared bottom line profitability is entirely smoke and mirrors, how, exactly, did it manage to book about €150m in bottom-line profits during 9M18 while also reducing NPEs by €2.4bn?

Furthermore, Eurobank made nearly €3bn of fresh loans during 9M18 (gross, not net of paydowns/write-offs). So the assertion that the bank's financial condition is hobbling its ability to provide support to the recovering Greek economy is clearly false. Yes, overall system loans are declining, but that is not because the banks lack the ability or willingness to lend, but instead reflects loan write-offs and ongoing deleveraging by customers. It is hard to see how the banks are spiralling towards a new crisis when liquidity conditions are improving, bad debts are falling, and banks are making new loans.

How/why are Greek bad debts shrinking?

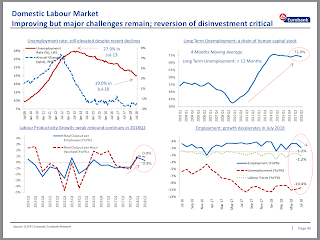

This organic decline in bad debt is occurring because - believe it or not - Greece's economy is starting to heal. GDP growth has now recovered to 2%, and unemployment, after peaking at 27% in 2013, has now declined to 18-19%, and continues to steadily fall. Relative to a 'full employment' levels of some 5% unemployment, this represents a 40% cumulative decline in 'excess' unemployment.

The recovery is occurring because, after a decade of painful rebalancing, enforced reforms, deleveraging and hard deflation, Greece has now corrected all of its major imbalances (excessively high government debt is the final issue to be dealt with - see further below). The current account and fiscal accounts are in balance (more on the latter later), and Greece's unit labour costs have now reverted to levels in line with/below its northern peers. This was the fundamental cause of Greek's economic woes in the first place. With GDP coming off depressionary lows, a recovery therefore should not be considered surprising, given that structural imbalances have now been redressed.

What about the existing mountain of bad debts?

But what about the existing mountainous stock of bad loans? While declining, Eurobank's stock of NPE (non-performing exposures) still remains at nearly 40% of its gross loan book (the 90 day past due NPL ratio is somewhat lower at 31% - down from 35% YoY). Surely the bank must be insolvent? There are two key factors that are often overlooked when high on-balance sheet bad loan data is thrown around, as it was in the article:

*Firstly, the existing stock of provisions held against those loans is being overlooked. In Eurobank's case, 54% of the carrying value of these NPEs (and 68% of NPLs) have already been provided for (i.e. written off against equity). That alone reduces the stock of unprovisioned NPEs to about 18%, or in financial terms, from about €17bn to about €8bn. The pace of negative formation, incidentally, is now running at more than €0.5bn per year, and the pace of core pre-provision profits also at nearly €1bn per year, so on current trends, the final €8bn could be fully resolved within 4-5 years, excluding the very important second point below.

*Secondly and very importantly, the existence of collateral is being completely ignored. Many of the bad loans carried on bank balance sheet have collateral held against them, including (most commonly) claims on real estate. The following chart shows, for instance, that 90% of consumer NPEs (often unsecured) are already fully written off, while only about 40% of mortgages have been. However, Eurobank estimates that, inclusive of collateral, the coverage rises to 111%.

Given that real estate prices have fallen about 40% peak-to-trough, this level of provisioning against NPE mortgage exposures is likely adequate or at least approximately adequate - particularly given that Greek real estate prices have finally started to rise again, for the first time in a decade.

Importantly, one of the reasons so many bad loans are still on the banks' books is that it has been very difficult for the banks to seize and liquidate collateral. When bad loans are completely charged off the books, it is usually an admission that no further recoveries are likely (e.g. when a company has been wound up, and all potential legal avenues for recovery have already been pursued). Collateral recovery and liquidation has taken far too long in Greece's archaic legal system. However, long-overdue reforms have now occurred which are allowing banks to more easily enforce their rights, and the pace of repossessed real estate auctions has sharply increased this year. This development is also reducing the incidence of 'tactical defaults' (where people don't bother to pay, reasoning that it will be too complex and time consuming for the banks to repossess the collateral). This is already starting to have a visibly positive impact on banks' NPE/NPL ratios.

In other words, just because these NPEs are still on the books, does not mean that their current carrying value (nominal less accumulated provisions) is necessarily less than the recoverable amount (although they could be) - particularly in a recovering economy. Eurobank, for instance, recently agreed to sell €1bn worth of impaired consumer loans, and it did so at a price that was capital and P&L neutral, suggesting carrying values were in line with their economic value. With pressure on Greek banks to reduce on-balance-sheet bad loans, the pace of sales is likely to continue to increase in coming years, which will likely allow them to demonstrate a much more rapid decline in on-balance sheet bad debts than many currently expect.**

It was for this reason that in 9M18, Eurobank was able to reduce its stock of NPEs by €2.4bn, and yet remain profitable. If their loan book was woefully under-provisioned, this would have been impossible. This is also how and why Eurobank expects to reduce its NPE ratio from above 40% to below 15% by the end of 2021, and to do so while remaining profitable, generating capital, and booking a declining cost of risk in the P&L, towards 100bp by 2021 (from a little under 200bp at present). Many do not believe that to be possible, but given existing provisions and collateral; improving collateral realisability; a healing economy; strong pre-provision profitability; and the ability to securitize and sell loans to investors, it is not at all unrealistic. Indeed, on current trends (there are various risks, of course), it is not only possible but quite likely.

That's not to say the Greek banks have fully written down all of their legacy bad debts to realisable value. If they had, the cost of risk would be negative during a period where NPEs were organically shrinking, and yet Eurobank has continued to take provisions at a cost-of-risk run-rate of nearly 2% (about €170m a quarter). This is the typical playbook where recovering banks use organic pre-provision profitability to write off legacy back-book bad debt, thereby slowly (but invisibly) recapitalising themselves through internally-generated capital. The game is to hid your bad debts long enough for internal capital generation to resolve the problem over time. This undeniably continues to happen. With nearly €1bn a year of pre-provision profits, and negative NPE formation trending a €0.5-1.0bn as well, Eurobank is in fact quietly recapitalising at a pace of €1.5-2.0bn per year.

However, the good news is that this has already been going on for a long, long time (not to mention the fact that several recapitalisations have also already occurred), such that a significant fraction of the process of provisioning for bad debt has already been completed. So how much more internal recapitalisation is needed, and does Eurobank have time?

As noted earlier, Eurobank's consumer loans are mostly written off (only €150m are unprovisioned), and the majority of its mortgage book is likely mostly provisioned and covered by mortgage collateral. However, the adequacy of provisions for SME and corporate loans are harder to assess. Gross exposure here are €9.5bn, and provisions are €5.4bn, leaving €4.1bn unprovided for. Many of these loans are also collateralized, however (often by real estate in the case of SMEs), and Eurobank claims provisioning for these loans is also 101-105%, inclusive of collateral.

As noted earlier, Eurobank's consumer loans are mostly written off (only €150m are unprovisioned), and the majority of its mortgage book is likely mostly provisioned and covered by mortgage collateral. However, the adequacy of provisions for SME and corporate loans are harder to assess. Gross exposure here are €9.5bn, and provisions are €5.4bn, leaving €4.1bn unprovided for. Many of these loans are also collateralized, however (often by real estate in the case of SMEs), and Eurobank claims provisioning for these loans is also 101-105%, inclusive of collateral.

However, let's assume that collateral will cover only 50% of the difference, such that Eurobank is €2bn short of provisions. On its current run-rate pre-provision profitability of nearly €1bn a year, it will take only two years to cover the shortfall, even assuming zero loan cures as the Greek economy recovers, which is unlikely. Even if it take three years, this is still well within the prescribed 2021 timeline Eurobank has agreed to with European authorities to reduce its NPE ratio to below 15%.

This is also where the Bank of Greece's SPV NPE resolution initiative is potentially interesting. The draft plan envisages banks exchanging bad loans at carrying value in exchange for the transfer of their (considerable) deferred tax assets. Many have feared that this plan could be negative for banks' capital, which - depending on how it was done, could be (as DTAs form part of capital, so would reduce capital if sold, whereas the loans would be sold at carrying value; however, a reduction in on-balance sheet loans would also reduce banks' risk-weighted-assets, reducing the amount of capital they need to hold).

However, importantly, Eurobank noted on its recent 3Q18 call that the plan is likely to be voluntary rather than compulsory, and they also noted that they did not believe new measures were required, as they were already highly confident in their ability to organically resolve bad debts in accordance with their existing plan. This means that the plan is all upside, and the bank could conceivably cherry-pick the worst and most underprovisioned loans on their balance sheet, and resolve them via DTA transfers, and only deal in a manner and scale where it is economically advantageous for them to do so. It may impair capital somewhat, but they would also have a choice as to how much to tender, so as to ensure they had sufficient capital post-transaction.

Far from being a last-ditch, futile attempt at financial engineering by the Greek state to stave off yet another banking crisis, as the Telegraph article suggests, this is actually a potentially sensible, creative, and opportunistic initiative that would improve the optics of Greek banks, while helping them monetise their significant DTAs, which are worth billions of Euros. Eurobank alone has some €4bn of DTAs, meaning that, based on the status quo, they will not need to pay cash taxes for a very long time. The SPV proposal floated by the Bank of Greece is actually a good idea, given that these DTAs have real value given that many of Greece's banks are actually highly profitable when the P&L impact of the write-off of legacy bad loans is excluded.

But isn't the Greek state bankrupt?

But what about the Greek state's financial position? With government debt-to-GDP at 180%, surely the Greek state is insolvent?

Greece's debt-to-GDP has stabilised at around 180% of GDP for about seven years now, as is evident below. This has occurred for four reasons. Firstly, a modest debt haircut was taken in 2012 by Greece's creditors. Secondly, harsh austerity measures, coupled with improved tax collection, has improved the fiscal balance to the point that the government's 'primary surplus' (i.e. surplus before interest payments on the debt) has reached 3.5-4.0% of GDP. This is a staggeringly high surplus for an economy at depressionary lows (equivalent to 1933 USA), and has been achieved at the cost of much hardship for the Greek people, in the name of long discredited, but nevertheless depressingly orthodox, economic ideology (Keynes is rolling in his grave). At a 3.5% primary surplus, the overall balance is 0% at a 2% effective interest rate on government debt.

Thirdly, Greece's Eurozone creditors (and the IMF) have provided (and continue to provide) significant support in the form of low-cost funding lines with long dated, deferred maturities, contingent on continuing reforms and harsh austerity measures. This has keep the overall cost of debt to the Greek government relatively low, and below the rates markets would have demanded (which did bankrupted the state in 2011), which has allowed the overall balance to approximate 0%. Existing agreements allow for Greece to continue to enjoy low rates and extended maturities on large portions of its debt over a very long period of time, contingent on robust primary surpluses being sustained.

And lastly, Greece's economy has stabilised in recent years, and recently begun to grow somewhat (about 2% pa at present). The denominator in the debt-to-GDP equation is therefore now stable to increasing.

Interestingly, Greek government debt is actually not unusually high on a per capita basis relative to other EU members - about €30k. What is instead unusual is that GDP per capita is so low, having fallen some 30% throughout a decade-long depression that has exceeded the US's Great Depression in its severity and duration. This means that if GDP per capita can recover over time to a more normalised level, the debt-to-GDP ratio could actually conceivably improve quite rapidly. If debt was held stable, and GDP grew a just 2% pa (and say 3% nominal) - a low rate off a very depressed base - within five years the ratio would have fallen to 155%, and a virtuous cycle will then start to kick in as debt levels continue to decline, as the interest burden falls relative to primary income/GDP, and eventually Greece would be able to access capital markets at lower interest rates as well. In addition, like many governments, the Greek state is asset rich, and a large swathe of privatisations are also planned in coming years, which will yield additional cash that can be used for deleveraging.

The improving financial health of the Greek state is evident in arrears clearance. Total arrears with respect to regular government disbursements reached as high as €7.3bn as recently as 2016, but has now fallen to €2.6bn. Once arrears clearance is over, additional funds will be available for deleveraging.

What about recent 'backtracking' on pension reform? Does Greece really have the political will to maintain its current elevated primary fiscal surpluses, so as to enable ongoing deleveraging? The nuance that has been lost in the recent media-storm is that Greece only proposed postponing pension reform in 2019 because the economy has done better than expected, and thus the primary government surplus is exceeding expectations (and agreed upon targets with Brussels). Consequently, the pension cuts are no longer necessary to meet primary surplus targets, and hence there has been no 'backtracking' on agreed budgetary cuts. Notably, Greece's creditors recently concurred and assented to the deferral.

This is hugely important. This is actually a sign the economy is doing much better than expected, and that Greece is on the cusp of ending what has now been a decade of harsh austerity, which has crushed the economy over the past decade. As austerity eases, and Greek government spending starts rising with the economy, rather than contracting, the economy will likely begin to recover more rapidly, which in turn will boost tax collection and allow Greek government spending to rise further still, even while sustaining robust primary surpluses. This is very positive. And yet markets - so accustomed to old narratives around Greece's failures of fiscal discipline, were not able to appreciate this nuance, as it was drowned out by preconceived notions.

International operations

Lastly, with respect to Eurobank specifically, also overlooked has been the fact that the company has very profitable international divisions, operating primarily in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Serbia. The international divisions are currently making about €150m a year in bottom-line profits. In addition, Eurobank recently reached an agreement to buy Piraeus Bank's Bulgarian subsidiary for €75m, which inclusive of synergies, is expected to boost profits by some €25m, bringing the total to €175m. These operations are self-funding, highly profitable, and growing. With a market capitalisation of some €1bn, Eurobank's share price can be justified by these divisions alone, placing zero value on Greece.

Historically, that has been justified, as the Eurobank parent has proven to be worth less than zero, having been recapitalised in the past in a manner that wiped out shareholders. However, as no further recapitalisation is needed, so today's buyer of Eurobank gets the Greek operation for less than free, which is currently making some €700m in PPoV, and which should be capable of earning some €400m a year net of taxes, after its cost of risk normalises from 2021-22. Eurobank's deferred tax assets of some €4bn will also be extremely valuable as Eurobank returns to profitability, ensuring the company will not pay cash taxes for a very long time.

Conclusion

The gap between the facts and the prevailing narrative has resulted in Eurobank's share price - despite very significant operational and financial progress across all metrics over the past three years - recently declining to new all time lows, and the stock now trades at just 0.2x tangible book value; 5x current earnings - even with the company's cost of risk currently being elevated; 1x PPoP; and about 1.5x pre-tax earnings based on a normalised cost of risk, while it will not pay cash taxes for many years. If things go according to plan, this could easily be a €2.50 stock in the next 3-4yrs (vs. €0.46 at present), which would represent about 1x tangible book, and 7.5x normalised pre-tax earnings.

The Greek banking sector is highly consolidated and controlled by just four players, which creates the opportunity for a highly profitable oligopoly to emerge from the carnage of the past decade, while a recovering economy will also provide opportunities for loan growth and new fee income streams. Longer term, it is quite possible Eurobank could end up trading at a robust premium to book.

There are risks, of course. The biggest risk is political. Incompetent EU leaders could attempt to force the banks into another unnecessary round of capital raisings, although that seems relatively unlikely, provided the current economic recovery trajectory continues. Domestic politics are also unpredictable with an election coming up next year, and it is possible the electorate derives inspiration from Italy and demands higher government spending (although this also seems unlikely).

Another flight of deposits offshore a la 2015 is also a risk - albeit a falling one as the banks and Greek economy heal - which would force the banks to rely once again on emergency credit lines from European authorities. The Greek economy could also always slip back into recession, and reverse the recent trend of asset quality healing. Rising regional bond yields are also a negative, as it will make it more difficult for Greece to refinance its government debt at affordable rates.

Another flight of deposits offshore a la 2015 is also a risk - albeit a falling one as the banks and Greek economy heal - which would force the banks to rely once again on emergency credit lines from European authorities. The Greek economy could also always slip back into recession, and reverse the recent trend of asset quality healing. Rising regional bond yields are also a negative, as it will make it more difficult for Greece to refinance its government debt at affordable rates.

Eurobank is not a low risk investment, nor is it for the faint of heart, given the stock's extremely high volatility. However, I like the odds at these prices. I am long.

LT3000

*For those so inclined, I recommend reading Eurobank's presentation materials in full. Eurobank's full 3Q18/9M18 results presentation can be found here.

**Ironically, but not surprisingly given how incompetent many EU regulatory authorities are, the pressure being placed by Brussels on Greek banks to reduce on-balance-sheet bad debts is actually likely to be - at the margin - negative for the health of the Greek banks and the Greek economy, as it will force them to sell loans quickly, and in doing so, places the banks in a weaker bargaining position that will likely result in them selling the loans more cheaply than they might otherwise have.

They are also being forced to sell them at exactly the point in the cycle where, if they held on to them, they might actually enjoy better than expected recoveries, as the Greek economy continues to heal. The pressure to reduce bad debts is therefore completely counterproductive.

Incidentally, it's a shame the world has so many incompetent people running so many important government institutions - why can a 36 year old nobody blogger see an obvious problem here that some of the most prestigious and powerful institutions in the world can't? It's depressing.

DISCLAIMER: The above is for informational/entertainment purposes only, and should not be construed as a recommendation to trade in the securities mentioned in this article. While provided in good faith, the author provides no warranty as to the accuracy of the above analysis. The author owns shares in Eurobank and may sell this position or buy more shares at any time without notice.

**Ironically, but not surprisingly given how incompetent many EU regulatory authorities are, the pressure being placed by Brussels on Greek banks to reduce on-balance-sheet bad debts is actually likely to be - at the margin - negative for the health of the Greek banks and the Greek economy, as it will force them to sell loans quickly, and in doing so, places the banks in a weaker bargaining position that will likely result in them selling the loans more cheaply than they might otherwise have.

They are also being forced to sell them at exactly the point in the cycle where, if they held on to them, they might actually enjoy better than expected recoveries, as the Greek economy continues to heal. The pressure to reduce bad debts is therefore completely counterproductive.

Incidentally, it's a shame the world has so many incompetent people running so many important government institutions - why can a 36 year old nobody blogger see an obvious problem here that some of the most prestigious and powerful institutions in the world can't? It's depressing.

DISCLAIMER: The above is for informational/entertainment purposes only, and should not be construed as a recommendation to trade in the securities mentioned in this article. While provided in good faith, the author provides no warranty as to the accuracy of the above analysis. The author owns shares in Eurobank and may sell this position or buy more shares at any time without notice.